Drone, Photogrammetry Map Hurricane Matthew Damage Florida after Hurricane Matthew Kwasi Perry, founder of UAV Survey Inc., recently completed a photogrammetric project in Florida after Hurricane Matthew, which resulted in 3D models of housing and transpo

- Details

- Category: Ingeniería mundial

- Hits: 1276

Geospatial analyst Kwasi Perry is founder and lead consultant at UAV Survey Inc., based in Houston. Perry puts a strong emphasis on educating clients. It has made all of the difference in supporting the success of his start-up. His strategy in a nutshell is to research a particular company, gain knowledge on how unmanned aerial vehicles (UAVs) —also known as drones — can help them, schedule an initial consultation with the company to present his findings, and then hopefully make a deal.

“By the time the presentation has ended, we’ll usually have a client. So we have about an 85 to 90 percent [rate] of turning that into business after that initial presentation.”

Perry has a bachelor’s degree in geography and geospatial science from North Carolina Central University and studied geoscience as a graduate student at Texas A&M University. He is a former federal geospatial intelligence analyst with deployment experience in both Iraq and Afghanistan, and launched his UAV company in September 2015. UAV Survey Inc. flies drones and collects aerial data for companies looking to contract out. It also offers procurement, training, consultations and certification assistance for companies interested in developing in-house UAV programs. Perry says his business is open to helping with pretty much any drone-related needs, but that it leans mostly geospatial because of his geospatial background.

Every job he has taken on thus far has involved drone-based photogrammetry and, thanks to his proactive approach of teaching about the value of his deliverable, he has attracted big-deal clients, mostly from government and academia. One example is a job he recently completed for the State of Florida.

Post-Hurricane Damage Assessment

The assignment was to collect aerial data by drone over parts of Florida immediately after Hurricane Matthew, which touched down in fall 2016. The acquired data would provide a quantifiable damage assessment that would illustrate the effects of Hurricane Matthew on infrastructure. The client was the State of Florida’s emergency response team. They contracted civil and damage assessment engineers from the University of Florida, which in turn contracted UAV Survey Inc. to handle the drone operation.The university reached out to Perry because he had worked with them before. He says they weren’t exactly sure what type of data he could provide going in, but they knew he could offer pictures and video at the very least. That’s when he told them, “While I could do pictures and video, and I will put that as part of your deliverables, I think we should go with a photogrammetry product, which is a 3D mesh, because it is detailed enough to see roof damage, where you can actually quantitatively assess roof damage size wise and everything.”

He was contacted about the project about two days before the hurricane hit Florida, so he flew to Gainesville, Fla., from Texas right away and left Gainesville once Hurricane Matthew had moved north of his assigned spots. The areas he was responsible for were Flagler Beach on the Atlantic coast and an area just south of Marineland, about 20 miles north of Flagler Beach. He says they arrived at Flagler Beach, the first stop, as soon as they possibly could while having daylight and safe weather conditions, before the winds moved things like shingles and tiles around too much.

Perry describes the setting as a typical coastal area, picturesque with homes not far off the coastline. The houses generally appeared unaffected by serious destruction, he says. Most of the residential damage was to roof shingles and tiles. However, the nearby A1A highway wasn’t so lucky.

“It totally destroyed the A1A highway. It was really bad from a civil infrastructure standpoint. It just totally eroded away and broke up the highway, which was recorded in absolute detail with our 3D model,” Perry says.

The Right Tools

Perry captured photogrammetric data and video of 25 acres of Flagler Beach and about 40 acres of the area near Marineland using a DJI Inspire 1 drone and an X3 12-megapixel camera with 4K video capability. For 25 acres, Perry says it took just 15 minutes to collect the needed data with the drone, then 13 hours to process it using Pix4Dmapper, all on his own. “So when you look at start to finish, it takes one day to get that product done and delivered. … I have an extremely powerful laptop. It’s 64 gigs of RAM, i7, has a desktop-grade graphics card in there. So it’s just as powerful as really strong desktops, but it’s in a laptop. So it allows me to process onsite if need be.”In the end, he delivered a 3D point cloud model, digital terrain model, and pre- and post-damage orthomosaics. While he did not have enough notice to capture pre-damage data himself, Perry was able to overlay his post-hurricane orthomosaic on pre-hurricane data from Google Earth. Because he had collected at 2-3-centimeter accuracy, he says it overlaid perfectly. It showed roof damage, scattered shingles, tiles, and aluminum and vinyl siding. “It is amazing because it gives an idea of just how bad things were afterward,” Perry says.

A vital aspect of getting the State of Florida a useful dataset from which they could effectively evaluate the impact of Hurricane Matthew was choosing the right tools.

From a UAV standpoint, he says you can spend as much money as you want in the drone world. He selected the DJI Inspire 1 because he views it as the perfect medium between capability and price for companies like his that are just starting off. An important question he asks himself is, “Can it collect the data like I need it to collect?” If the answer is yes, he says there’s no need to pay for more bells and whistles. Perry also likes the portability of the drone. He says the smaller, more packable and accessible UAV seems to be the wave of the future and that he definitely sees the technology getting better there.

“It gives you enough to create a proof of concept and do the type of jobs to get investor confidence so they can say, ‘If this is what he’s doing with this, if we put in some money we can get the other platforms as needed and really go from there.’”

For data processing, Perry says he chooses Pix4Dmapper for ease of use. He has an unofficial relationship with Pix4D because he uses their product so extensively. He likes that the software can be as simple or as detailed as desired by changing the settings. “It’s a very powerful and flexible platform. Somebody new can use it right away and somebody experienced can get even more out of it.”

Going Global

With the project being as short-notice as it was, Perry says he is very happy with the turnout. The challenges were not so much technical as they were administrative. “The unique part of it was the actual event that happened, but everything else geospatially, even though I didn’t actually do that [kind of project] before, I understood it in my head before we even went out there.”The approach to accessing the site was new for Perry because he arrived before residents were allowed to return. He was given a placard and tag for his car that read “State of Florida Emergency Response Team,” which gave him authorization to get past National Guard and police roadblocks.

Speaking of law enforcement, he says the legal aspect of operating a drone and gaining acceptance from authorities is probably the biggest challenge he runs into. He expects this to continue into the foreseeable future. What he worried most about on the trip wasn’t data acquisition or processing; it was, “Will law enforcement allow us to do this?” He says law enforcement isn’t always knowledgeable of the rules surrounding drone operation and the permissions Part 107 and Section 333 exemptions give. “They can make the final decision and say, ‘This paperwork may look good, but I don’t want you flying,’” Perry says.

In a situation like this, he says the smart thing to do is listen and come back to fly another day. It isn’t worth putting the business in jeopardy. This is an important reason to have a thorough understanding of what can be done under whichever Federal Aviation Administration (FAA) certification or exemption one has, he points out. “At the very least, you may be able to talk to them. It’s really good for you to know what you can do, why you can do it and be able to explain it in a manner that’s not inflammatory. … Sometimes it’s just a matter of education to law enforcement and they’re like, ‘Oh, OK. I see what you mean.’ So you really have to be an ambassador for the UAV community.”

This level of professionalism and eagerness to explain, which Perry also applies to clientele, has helped him reach a huge milestone. In his initial business plan, his ultimate aim was to go global. Now, just over a year after launching UAV Survey Inc., he has taken on his first international project. Not long after his Florida project, he was contacted by the University of Notre Dame about collecting and processing data for a site affected by Hurricane Matthew in Haiti.

“It ended up working extremely well where they were excited and shared this with their colleagues at other universities. So, coincidentally, that’s how the thing in Haiti started. It was driven by the work that I did and the product I delivered to the University of Florida, and then from there the State of Florida.”

Jueves 12 de enero del 2017

Using 3D Printer Technology to Represent Survey Information

- Details

- Category: Ingeniería mundial

- Hits: 696

The Art of Bathymetry

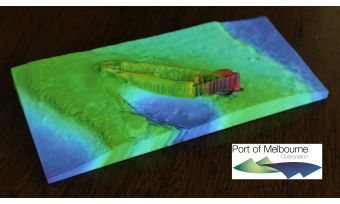

Great advancements have been made in three dimensional printing over the last few years and have made an impressionable impact across a variety of industries. 3D printing's versatility can be incorporated into any industry that has some form of three dimensional design. An exciting application is to model point clouds from survey techniques to create three dimensional scaled models for visualisation and communication. This article explores a new medium using 3D printed technology.

(By Andrew Ternes, Port of Melbourne and Dr Daniel Ierodiaconou, Deakin University, Australia)

Over the last few years great advancements have been made to all forms of surveying in three dimensional data capture, whether it be multibeam echo sounders in hydrography, laser scanning in terrestrial and bathymetric surveying or photogrammetry through aerial surveying. Three dimensional data capture techniques produce vast amounts of information in the form of a point cloud from which useful information can be extracted. The information is usually translated to a two dimensional format in the form of a computer aided drawing (CAD), a Chart, a two and half dimensional digital format for visualisation or analysis to derive secondary products such as terrain metrics.

To convey three dimensional form cartographer’s employ varying techniques including colour gradients, contours, relief or sun shading to show variations in depth and the use of oblique angles instead of the typical orthogonal view. These techniques are not usually misinterpreted by spatial professionals but can be difficult for non-spatial individuals to comprehend. Colour gradients have varied elevations being represented by different colours, which can be difficult to interpret, particularly if a legend has not been provided. Shaded relief or shadowing can provide extra information to the viewer but has been known to cause optical illusions where depressions can appear as rises and vice versa. The use of oblique angles from a set perspective can show form, but may hide points of interest depending on the complexity of the information. The oblique angles are usually static images or displayed as a digital model that can be navigated on a computer, with a screen that is still two dimensional.

Utilising multiple open source software that was designed for GIS, point cloud manipulation and 3D modelling & animation; datasets captured by the Port of Melbourne Corporation and Deakin University were designed into 3D models and then sent to a 3D printing service provider.

An initial learning phase was required to learn the various software programs required to manipulate the point cloud data into a 3D model suitable for print. The point cloud is either turned into a surface as a Digital Terrain Model (DTM) or a Triangular Irregular Network (TIN). A surface cannot be printed alone, as it is too thin to be considered printable by a 3D printer, so a 3D polygon or a cube is used to enclose the surface. The surface is then used as an intersecting plane using Boolean logic, anything above the surface is deleted while everything below is kept, resulting in an impression of the surface on the top of the 3D polygon, while leaving a flat base for ease of display. Orthometric photos or images of the modelled area can be used to apply textures to the model by wrapping around it and providing contextual information (Figure 1).

Important points to consider in creating a dataset to be 3D printed

Choose the right 3D printer for your intended purpose and associated material, which can vary from plastics to colour coded layered sand with epoxy. The models you see in this article have all been printed using the Shapeways 3D print service utilising ‘Full colour sandstone’. The material was chosen for its durability and its ability to display multiple colours. When creating a model to be 3D printed, the printer’s capabilities needs to be taken into consideration. For instance, the maximum printer dimensions for the models shown here were 250 by 380 by 200 millimetres with a resolution of 0.4 of a millimetre, but can vary by printer type and material used. This influences the scaling of the model to the printer dimensions and the level of detail you will be able to see in the final print. Resampling the dataset to a coarser resolution may be necessary if trying to model a large area. The model of Eliza Ramsden was at a resolution of 0.25m with an area of 5,577m2 (Figure 2) whilst the Port Phillip heads were modelled at 20m with an area of 93km2 (Figure 3). In our case, models had to conform to printer provider accepted file formats and restricted to file sizes of 64MB or 1 Million polygons. The 1 million polygon restriction can be problematic when trying to balance terrain size and detail. For coloured prints we found the best formats to use to be VRML and X3D, whilst for non-colour prints STL, OBJ and Collada were appropriate but likely to vary according to format requirements by print services.

Another apparent problem had to do with applying the colour. The colour was captured using an orthogonal geotiff of the survey areas with some of the models having the land terrain masked with aerial photography instead of a bathymetric colour scale. Using an open source 3D animation program the geotiffs were draped over the elevation models using a process called UV wrapping. There was not a single program that can handle all the processes to create a 3D print and was therefore a combination of several programs, all with different intended purposes. Hopefully in the future survey software can adopt some of the formats and functionality to future versions of their software for standard 3D print formats.

The methodology has been applied to multibeam bathymetry, UAV captured Photogrammetry and DSM models, terrestrial and bathymetric Lidar data and satellite derived elevation data either as a single dataset or combination of multiple datasets to form a comprehensive model. The final models are not limited to being 3D printed and have been used in other 3D virtual viewing mediums and show promise as communication tools for the rapidly developing field of augmented reality. The Augment website and mobile phone application allow the models to be uploaded and shared. A tracker can be a customised information sheet that can include the company logo or a simple Quick Response (QR) code. When the application is run on your device it reads the QR code or the unique layout and overlays the 3D model over the camera view, allowing the user to explore the model (Figure 4).

Dr Ierodiaconou from Deakin University, School of Life and Environmental Sciences, Warrnambool, Victoria has been exploring the value of 3D printed models as communication tools (Figures 5 and 6). He found an immediate benefit with 3D printable products for communication of environmental values. This includes the application of low cost unmanned aerial vehicles for defining endangered hooded plover habitats on nesting beaches funded by Birds Australia. The first model (Figure 5) shows storm cut of the beach face whilst providing quantitative spectral and elevation data tied to a datum using RTK GPS (Real Time Kinematic GPS). Time series analysis allows the investigation of management interventions such as the spraying of the invasive Marram grass that has been linked to stabilisation of mobile sand dunes and steepening of the beach face. The second model (Figure 6) shows the integration of terrestrial imagery and elevation combined with high-resolution seafloor mapping data (10cm resolution) of Refuge Cove, a popular anchorage on the east coast of the most southern tip of mainland Australia. The project was funded by Parks Victoria and multibeam sonar data was captured using a Kongsberg 2040C fitted to Deakin’s 9.2m research vessel Yolla. “We find it an amazing way to communicate the value of marine ecosystems, showing a direct link to the terrestrial realm with continuation of headlands and drowned coast and river features from lower sea level stands”.

The Port of Melbourne Corporation use the models at sponsored events and festivals, and the response from the public is invariably positive. “It’s always more effective to show, rather than tell, especially when discussing something that cannot ordinarily be seen, and the 3D models are very effective engagement tools in this regard. These 3D models can provide an immediate sense of spatial relief with minimal interpretation or miscommunication through cartographic techniques especially when communicating with non-spatial professionals” Ierodiaconou said. Whilst three dimensional fly throughs will always have a place in science communication (see an example from Wilsons Promontory Marine National Park) new communication mediums provide exciting opportunities whether in hard print where you can feel the texture of the spatial domain or augmented reality for immersive experiences with unlimited field of views.

Miércoles 21 de diciembre del 2016

¡Sorpresa! La materia oscura «imita» a la ordinaria

- Details

- Category: Ingeniería mundial

- Hits: 674

Parecen galaxias espirales corrientes, como nuestra Vía Láctea, solo que diez mil veces más pequeñas. Y han sido estudiadas a fondo por Paolo Salucci y Ekaterina Karukes, de la Escuela Internacional de Estudios Avanzados de Trieste, (SISSA), en Italia. ¿La razón? Estos objetos, según el propio Salucci, podrían ser "el portal que nos lleve hacia una nueva física, más allá del Modelo Estandar, y nos permita explicar qué son la materia y la energía oscuras".

Por primera vez, estos investigadores han estudiado estas pequeñas galaxias estadísticamente, aplicando un método que elimina las variaciones individuales de cada objeto y revela, en conjunto, las características generales de esa clase de galaxias. "Hemos estudiado 36 de estas galaxias -afirma el investigador-, un número suficiente como para aplicar técnicas estadísticas. Y al hacerlo, encontramos una relación entre la estructura de la materia ordinaria, la que hace que las estrellas y las galaxias brillen, y la materia oscura".

Como sabemos, la materia oscura es uno de los mayores misterios della Física. Dado que no emite ninguna clase de radiación elecgromagnética, no puede ser detectada por instrumento alguno, ni siquiera por los más modernos y sofisticados. Pero la materia oscura responde a las leyes de la gravedad, y conocemos su existencia, precisamente, gracias a la acción gravitatoria que ejercen sobre la materia que sí podemos ver. Se ha calculado que la materia oscura es cinco veces más abundante en el Universo que la materia ordinaria. En palabras de Salucci, la materia oscura "solo interactúa con la materia ordinaria a través de la gravedad. Nuestras observaciones, sin embargo, dicen algo muy diferente".

En efecto, Salucci y Karukes han mostrado que, en las galaxias observadas, la materia oscura "imita" a la materia ordinaria y visible. "Si para una masa dada -afirma el investigador- la materia luminosa está muy densamente compactada, lo mismo sucederá con la materia oscura. De forma similar, si la materia ordinaria está más repartida que en otras galaxias, también lo estará la materia oscura. Se trata de un efecto de imitación muy fuerte y que no puede ser explicado usanto el Modelo Estandar de Partículas".

Problemas del Modelo Estandar

El Modelo Estandar es la Teoría que explica de qué está hecha la materia (ordinaria) y goza de una enorme aceptación por parte de la comunidad científica. De hecho, explica las fuerzas fundamentales de la Naturaleza y las partículas que las transportan (como los fotones, que son las partículas mensajeras de la luz) con una extraordinaria precisión. Sin embargo, el Modelo Estandar presenta varios aspectos problemáticos, especialmente el hecho de que no incluye a la gravedad. Y la existencia de fenómenos como la materia oscura y la energía oscura han dejado más que claro a los científicos que debe existir "otro" tipo de física aún por descubrir y explorar.

"A partir de nuestras observaciones -afirma Salucci- el fenómeno, y por lo tanto su necesidad, es increíblemente obvio. Y esto puede ser el punto de partida para explorar un nuevo tipo de Física. Incluso en las galaxias espirales más grandes encontramos efectos similares a los que hemos observado, pero se trata de señales que podemos tratar de explicar utilizando el Modelo Estándar a través de los procesos astrofísicos del interior de estas galaxias. Con las mini espirales, sin embargo, no existe una explicación sencilla. Estos 36 objetos son la punta del iceberg de un fenómeno que probablemente se está repitiendo en todas partes y que nos ayudará a descubrir lo que aún no hemos podido ver".

Lunes 19 de diciembre del 2016

La prueba de que la nada no está vacía

- Details

- Category: Ingeniería mundial

- Hits: 669

El proyecto parte de un reto, una carrera científica propuesta por Google. Se trata de enviar un rover, un robot rodante teledirigido, a la Luna, conseguir que recorra un mínimo de medio kilómetro de superficie lunar, tomar fotos y vídeo en alta definición y enviar el material de vuelta a la Tierra. El primero que logre cumplir ese objetivo antes de diciembre de 2017 ganará los 20 millones de dólares del premio Lunar XPrize. Y un grupo de científicos alemanes, apoyados por la ingeniería de Audi, se ha apuntado a la carrera. Pretenden situar su robot en el cráter denominado Littrow, en un punto lo más cercano posible al lugar donde aterrizó la misión Apolo 17 y, ya que están allí, hacerse con material gráfico que demuestre, de una vez por todas, que el hombre sí estuvo en la Luna.

Tendrán que darse prisa y llegar antes que otros dos equipos científicos que ya han contratado incluso el lanzamiento, la compañía californiana Moon Express y una organización sin ánimo de lucro israelí llamada SpaceIL. El robot ya está listo y los preparativos avanzan a toda velocidad.

El robot alemán se llama Lunar Quattro y es de aluminio. Ha tenido que perder 8 kilos desde su diseño original y el peso es de 35 kilos, incluyendo las tres cámaras 3D. Está dotado de cuatro ruedas que se mueven libremente en 360 grados y un sistema de placas solares que puede orientarse para captar la máxima cantidad de luz solar. Audi ha aportado su experiencia en tracción «quattro», así como sus conocimientos en construcción ligera y tecnología de propulsión e-tron. Finalmente, ha cedido este diseño a un equipo científico llamado «Part Time Scientists» que es el equipo que compite.

Si todo sale bien, Lunar Quattro aterrizará a 3 kilómetros de su antepasado Apolo y solo podrá inspeccionar la zona a 200 metros de distancia, porque la NASA exige preservarla para la posteridad. Sus creadores aseguran que aun a esa distancia será capaz de escanear el vehículo del Apolo 17 y evaluar su estado. Eso nos permitiría saber, por ejemplo, qué tipo de daños han podido causarle la radiación durante las últimas cuatro décadas o qué efecto han tenido en los materiales las temperaturas, los micrometeoritos…

Michael Schöffmann, el coordinador de desarrollo del proyecto, ha declarado que «la colaboración con el equipo de científicos ha sido muy enriquecedora, estamos rompiendo barreras tecnológicas y podremos aprender todavía mucho más».

Lunes 19 de diciembre del 2016

Los sables láser

- Details

- Category: Ingeniería mundial

- Hits: 669

En «Star Wars» hay un Universo lleno de civilizaciones alienígenas que conviven en un precario equilibrio. Las batallas pueden implicar a gigantescas naves espaciales y a soldados armados con potentísimas armas. En medio de ese caos, hay caballeros capaces de manipular las reglas de la física y pilotos capaces de moverse entre dimensiones. ¿Quién no querría vivir algo así en el mundo real? ¿Sería esto posible?

Una de las primeras cosas que haría falta para hacer un viaje al Universo Star Wars sería, evidentemente, un buen sable láser. Son capaces de cortar a cualquier enemigo o incluso atravesar una gruesa plancha de metal con facilidad. Si la situación se pone complicada, tambien pueden hacer rebotar disparos láser. Por desgracia, la física del Universo «real» se lo pone muy difícil a los sables láser. ¿Por qué?

-La luz atraviesa la luz: Tal como explica el documental «¿Puedes construir un sable láser real?» de Michio Kaku, uno de los primeros problemas que aparecen es que la luz no tiene masa ni sustancia, así que las «hojas» de estos sables jamás entrarían en contacto. Sería como hacer un combate con linternas de aspecto bonito.

-El láser no se detiene: la luz láser sigue su trayectoria hasta que se encuentra con un obstáculo en medio, tal como se explicó en Physics.org. Los sables láser podrían ser en realidad lanzas de varios kilómetros de largo, capaces de acabar con la cabeza de cualquier compañero de batalla. Una opción sería poner un espejo al final del sable, pero entonces ya no se podría cortar a nadie sin romper el dispositivo. También podría ser que el enemigo usase espejos como arma de defensa contra láseres, y que incluso los usase en nuestra contra.

-Haría falta un reactor de bolsillo: También se puede considerar que estos sables están hechos de plasma (gas a una temperatura extremadamente elevada) mantenido en una especie de campo de fuerza. El problema aquí es que la tecnología necesaria para generar toda la energía para producir el plasma y contenerlo requeriría inmensas cantidades de energía solo producidas hoy en día, y en teoría, por un gran reactor. ¿Podría llevarse algo así en el espacio de un empuñadura?

-El plasma estallaría: En todo caso, cuando dos sables de plasma chocasen, sufrirían probablemente un fenómeno de reconexión magnética. El resultado sería una explosión de plasma de preocupantes consecuencias para el esgrimista. También cuesta imaginar materiales capaces de soportar temperaturas tan elevadas para la empuñadura y demás componentes; de momento las cerámicas usadas por la NASA soportan temperaturas de hasta 4.000 grados centígrados.

-La luz no hace ruido: pocas cosas hay más inconfundibles en Star Wars que los sonidos de los sables láser. Por desgracia, un sable real sería totalmente silencioso, porque la luz no hace ruido. Probablemente también sería medio invisible, salvo que a su paso se encontrase con partículas de polvo o gas. ¿Pero quién vería una película con combates de sables invisibles y silenciosos?

Lunes 12 de diciembre del 2016